Century: 100 Years of Black Art at MAM surveys far more than seminal artworks by visionary Black artists over the last hundred years; it also honors the profound beauty and unrivaled ingenuity of everyday Blackness. Along this spectrum between the eminent and the quotidian, we observe the social constructs, cultural innovations, and political gestures that have largely shaped Black life. Curatorially, we study these not as chronological phenomena to be subsumed by the dominant art historical narrative but rather as a constellatory body of evidence that testifies to the African diaspora’s enduring pursuit of spiritual sovereignty and refusal to be governed by Western conventions. Within the Black cosmos that is Century—where “century” is not a measurement of linear time, but rather a conceptual container to hold a rich cross-section of works from MAM’s collection that claim unapologetically Black space—we champion the subversive circuity of the Black radical imagination. Here, we are author and protagonist, the seer and the seen, and bold innovators of a spacetime continuum all our own.

While the cultural origins of time date back to ancient Egypt—and the sundials, water clocks, and astronomical practices designed by African people to live in harmony with the Earth and its seasons—timekeeping is not commonly spoken of as a Black invention. Rather, having been colonized by the West and repurposed as a tool of governance and oppression, timekeeping is often only attributed to Black Americans in the derogatory. Around the onset of the century that this exhibition surveys, Colored People’s Time—or CPT as it’s known in African American Vernacular English (AAVE)—emerged as a colloquialism to typecast Black people as habitually late and lazy. While CPT was in fact coined and circulated within the Black community itself, the dangerous stereotypes behind it have roots in the Antebellum South and the language slave owners used to dehumanize and devalue the people of African descent that they owned as property.

A little over a century after the so-called abolition of slavery, Black Literature professor Ronald Walcott published an essay in Black World Magazine entitled, “Ellison, Gordone, Tolson: Some Notes on the Blues, Style & Space.” In it, he repositioned Black people as keepers of their own time and holders of their own space, while recontextualizing CPT not as a derogation but rather as the strategic outcome of what I’ve termed Black spatiotemporal resistance. He argued, “CP Time actually is an example of Black people's effort to evade, frustrate and ridicule the value-reinforcing strictures of punctuality that so well serve this coldly impersonal technological society. Time is the very condition of Western civilization which oppresses so brutally. Yet if one, obviously, can no more evade time than one can escape from oneself, one can still seek to minimize its effects, which can only be done by finding solid ground on which to defend oneself, on which to operate.”[1]

This notion of defending against the violence of Western time and mitigating its negative impacts through resistance, innovation, transcendence, and the creation of cultural refuges is a central thesis of this essay. Unpacking both the rich cultural activity and active mechanisms of oppression that might prevent Black people from adhering to imposed strictures of punctuality, this research pulls forward for observation artworks that upset Eurocentric constructs of time and subjecthood. First, it will consider how Black artists have used photography as a worldbuilding device, reclaiming stolen time and forging safe space for Black culture to continuously reinvent itself. Second, it will observe vignettes of radical rest and leisure where Black interiority is expressed without inhibition and time stands still within safe spaces of our own creation. Across both areas of exploration, time is repatriated to its origins in the Black radical imagination and stripped of its colonial uses, and Black artists are celebrated for envisioning portals to transcend worldly limits, manifesting Black planets free from the often-oppressive gravity of whiteness.

Black Worldbuilding Through Photography

Throughout America’s sordid political history, Black photographers have demonstrated that capturing the breadth and depth of Black life against what writer Zora Neal Hurston termed, “a sharp white background,”[2] takes immense cultural aptitude. It demands the capacity to see art not only as a mirror reflecting what’s readily visible on society’s surface, but also as a multidimensional portal to rich countercultures and parallel universes. Considered two of America’s most influential Black photographers, James Van Der Zee and Gordon Parks feature in MAM’s collection as both historical anchors of the Black documentary photography tradition and as artists whose avant-garde aesthetic approaches transformed the very medium itself. Together, they augmented photography’s capacity to represent the plural dimensions of Black life and documented the myriad nuances of Black identity.

Long before the Western canon was able to perceive Black photography as art, let alone the lives that it documented as art worthy, Van Der Zee was celebrated within the Black community as a leading artist of his generation. He dutifully chronicled the Harlem Renaissance and its leaders, alongside the lives of everyday Black people, with technological precision and aesthetic innovation. In Van Der Zee’s Portrait of a Young Woman, 1930—which embodies the unique care that he brought to his craft—the artist adds a luminescent bracelet and ring to his sitter by hand-drawing directly onto the film negative, and further embellishes the print through applying rich greens, oranges, and pinks to accent natural elements within the composition (Fig. 1).

Across his expansive body of work, Van Der Zee used these same methods to balance shadows, retouch imperfections, and add fictional narrative elements that he felt augmented his sitters’ distinct auras. By transforming these staged portraits into transcendent works of art that imagined whom his subjects might be, free from the stereotypes imposed by dominator culture, he honored the rich complexities of Blackness and preserved the fluidity of Colored People’s Time. Additionally, by cultivating his Harlem studio as a safe space for Black people to express their intersectional identities, particularly amid the social upheaval and cultural reinvention of the Great Migration, Van Der Zee demonstrated the important role that art and artists played in shaping Black American culture in the wake of slavery.

While Van Der Zee’s commissioned studio portraits are celebrated as his defining contribution to the art historical canon, it was his mass-produced newspaper photographs, such as this one held in MAM’s collection and published in Negro World in August, 1924, that—as art history professor Emilie Boone asserts in her essay, “Reproducing the New Negro: James Van Der Zee’s Photographic Vision in Newsprint,” published in the Smithsonian’s American Art in 2020—“expand[ed] the possibilities of the role of photography during the New Negro era.”[3] A lesser-known yet historically significant body of work, these images, especially when viewed in aggregate, claim necessary space within the dominant historical narrative for a fuller, more authentic representation of Black public life (Cat. 1).

Here, Van Der Zee documents a group of Black Cross Nurses marching during the 1924 Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) Annual Convention Parade that celebrated the birthday of its founder, Pan-Africanist leader Marcus Garvey. The image, alongside the numerous others produced during Van Der Zee’s contract as the UNIA’s exclusive photographer, bears witness to a culture reinventing itself within the Black mecca of Harlem. As Boone argues, Van Der Zee’s photographic vision helped the UNIA to “regain the appearance of unity and progress,” and “establish a particular visual representation of the New Negro as a Black populace pridefully inhabiting its space.”[4] Van Der Zee bravely deployed photography in the creation, representation, proliferation, and ownership of unapologetically Black space, mobilizing a strategy of Black spatiotemporal resistance in Harlem with ripple effects that could be felt across the African diaspora.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, multidisciplinary artist Todd Gray similarly uses photography to establish a particular visual representation of Blackness and map altogether new spatial and temporal relationships within the African diasporic consciousness. Euclidean Gris Gris (Tropic of Entropy), 2019, consists of four framed prints, sourced from the artist’s personal archive, that are expertly manipulated and juxtaposed to evoke a palpable tension between the legible and the illegible, the objective and the subjective, and the real and the imagined (Cat. 64). Two rectangular photographs of lush Ghanaian foliage, washed in bright blue and neon pink color blocks, frame the overall composition which ascends skywards from the lower left. Between them sits an ovular image of a historic statue standing in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, the view of which is partially eclipsed by a tree in the foreground whose green leaves contrast with the transitioning yellow leaves of a tree in the background that litters the otherwise manicured garden. At the top of the composition floats a circular image, shot by the Hubble Space Telescope, of a celestial body cast against the infinite blackness of deep space.

This work is part of a series that compares geometrically designed European gardens with indigenous African landscapes to expose living legacies of colonialism, reimagine power relations between Africa and the West, and contrast constructs of beauty with the raw beauty of the natural world. Through his stacked, somewhat sculptural compositions, Gray intrepidly weaves together disparate elements, across time and space, to disrupt the linearity of history and subvert Western notions of causality. While the work is conceptual in nature, its title speaks concretely to Black spatiotemporal resistance: Euclidean refers to Western, geometric spatial prescriptions; Gris-Gris references an African Voodoo amulet endowed with protective powers; Tropic denotes a specific longitudinal or latitudinal position; and Entropy conjures a state of uncertainty shaped by forces of disorder. The artist’s profound use of poetics, coupled with his literal reframing of cultural binaries and iconographies, assert Black conceptualism as a powerful aesthetic strategy of resistance.

Nearby, Lorna Simpson—who began her career as a documentary photographer and moved on to conceptualism, carrying the tenets of documentary practice with her—similarly engages visual poetry to disrupt Western conceptions of time and space. In Coiffure, 1991, Simpson presents a horizontal triptych of black-and-white images that use the time-consuming photogravure printing method to cast her portraits against an inky black background (Cat. 33). On the left is the portrait of a woman with short natural hair, captured from behind, who wears a black top revealing her bare upper back. The central image is of an immaculately braided crown, looped in four concentric circles. And on the right is an image depicting the interior of a decorative African wood mask with a hanging wire running along its width.

The atypical perspective in these portraits—just like Simpson’s subversive use of cropping to “resist traditional ways of presenting the black female body while nevertheless insisting on her presence"[5]—is important in that it, like Black photography itself, reveals what’s behind or underneath Black subjectivities, as opposed to what’s merely legible on the surface. Beneath the triptych rest ten engraved plaques resembling object labels found in a museum, whose words annotate a script: “braid into four circles,” and “part into eight sections for the crown,” and so on. The ten plaques denote steps in a process, marking an abstract quantity of time while also conjuring the existence of concrete space, where two bodies might meet to perform these acts as an identity-affirming ritual.

That same year, Simpson produced a vertical triptych—Counting, 1991—which uses the image of the braided crown as a visual anchor, atop which she stacks the screen-printed image of a South Carolina smokehouse akin to those formerly used to house slaves; notably, the repetitive patterns found in the coiled braid are mirrored, albeit abstractly, in the circular brickwork of the structure (Fig. 2). Atop these, Simpson places the portrait of a woman, this time wearing a white top, captured from the front, and cropped just above her lips. The images are accompanied by texts that either mark the passing of time or allude to the construction of space: a series of time blocks caption the portrait of the woman; “310 years ago” and “1575 bricks” caption the image of the smokehouse; and a tally of twists, braids, and locks caption the image of the braided crown.

Across both works, Simpson improvises visual taxonomies and experiments with systems of enumeration that recall “the systems of documentary and anthropological photography in which pictures are regarded as evidence,”[6] while concurrently questioning the linearity of history and evidencing Colored People’s Time as a tool of its subversion. In the artist’s own words, these strategies are informed by her desire to “challenge the idea of subjectivity,” itself and to question “how we come to know the subject, and our desire to know the subject through details.”[7] Simpson's nuanced photographic explorations deliver us now to a discussion on the pervasive gaps and reductive tropes in popular representations of Blackness across history.

Black Leisure and Interiority as Resistance

In The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture, author Kevin Quashie explores these representational gaps, observing how popular depictions of Black culture often focus on performative Blackness and public gestures of resistance while overlooking intimate rituals and domestic expressions of interiority, such as those so boldly captured in Simpson’s work. He states, “The representation of black subjectivity as resistant has become a convenient simplification of what is surely more complicated; it is an easy template that does not encourage deeper, closer interrogation of cultural texts and moments. Our understanding of black culture becomes flat, and our sense of what characterizes black representation appears as a list of familiar terms—expressiveness, resistance, colorful, loud, dramatic, doubled. What would it mean to consider black cultural identity through some other perspective, like quiet, like interiority?"[8] Quashie’s prompt encourages us to consider the fraught historical relationship between Black expression and publicness—such as that captured across Van Der Zee’s work—while examining the outsize yet underrated role quietude and interiority play in shaping one’s identity and relation to self.

In unpacking this thesis, Black leisure becomes a launch point for the exploration of the rich inner life of a people systemically denied both the freedom of expression and the right to rest. Leisure is predicated upon access to free time, the resources to use that time for enjoyment, and the freedom of choice to do so in a self-defined way. As such, it’s no wonder that—in a country built upon the enslavement of Black people, the exploitation of their labor, and the extraction of their numerous resources—the sociological concept of Black leisure has remained as elusive as its materialization. Early portrayals of freed Black Americans often mistook self-care for indolence, and, in the wake of slavery, Black Codes emerged as a political tool to further govern our right to leisure. From controlling our movements through public space to dictating when and where we could congregate, Black Codes suppressed our human rights and freedoms in practice.

As independent historian Alison Rose Jefferson asserts in the curatorial statement for her exhibition, Black California Dreamin’: Claiming Space at America's Leisure Frontier, on view at the California African American Museum in 2023, “access to nature, recreation, and sites of relaxation—in other words, leisure—is critical to pursuing the full range of human experience, self-fulfillment, and dignity.”[9] Even under segregation and other tactics of racial persecution within the public realm, Black people boldly enacted leisure practices within their own homes and neighborhoods. From intimate weekend afternoons spent shaping rich oral history traditions on front porches, to late nights spent improvising jazz licks and blues riffs in packed clubs and speakeasies, we have situated Black identity within the specificity of our own cultural traditions, and pursued self-fulfillment against sizeable odds.

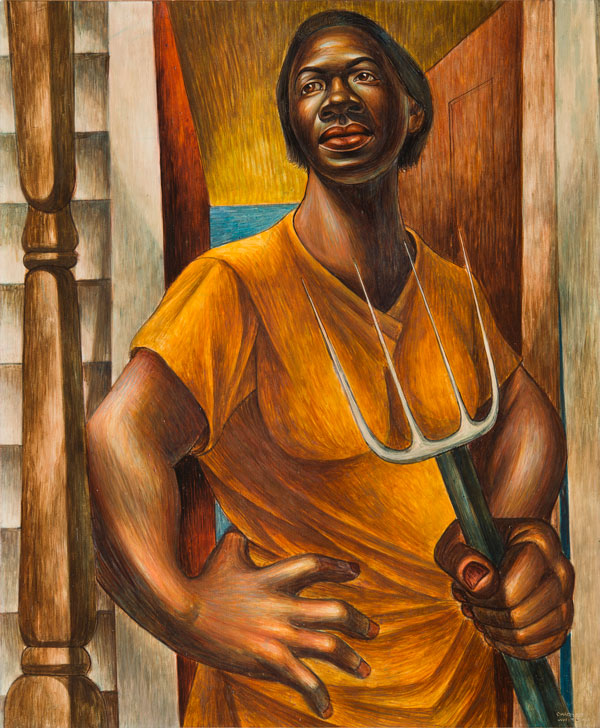

The life and work of American sculptor William Edmondson—who was born to freed slaves in Tennessee during the dawn of the Jim Crow era and went on to become the first Black, self-taught artist to have a solo show at MoMA in 1937—holds the many tensions and contradictions of what it meant at that time to be a free Black person in pursuit of dignity. Along his path to becoming a successful artist-entrepreneur who sold tombstones chiseled from discarded pieces of limestone out of his backyard, Edmondson worked at a hospital, a railroad company, and a stonesman’s studio, where he likely learned to wield the railroad spikes and hammer that he used to fashion his minimalist yet monumental sculptures. In Po’ch Ladies, 1941— “po’ch” being AAVE for “porch”—Edmondson depicts a pair of women, presumably sitting on their front porch, a familiar sight across Nashville’s numerous Black neighborhoods (Cat. 3). They gaze forwards—one with her arms crossed low across her lap and the other with her right hand draped pensively across her heart—observing what one imagines are passersby on the street in front of them. Despite their body language’s evocation of a broader scene, the two are clearly embedded in an intimate, leisurely moment of connection.

In her New York Times article, “On the Front Porch, Black Life in Full View,” journalist Audra D. S. Burch discusses the cultural and narrative importance of the porch, stating, “In its framed simplicity, the front porch has been a fixture in American life, and among African-Americans it holds outsize cultural significance…the front porch has served as a refuge from Jim Crow restrictions; a stage straddling the home and the street, a structural backdrop of meaningful life moments. It is like the quietest family member; a gift where community lives and strangers become neighbors.”[10] Here, Burch gives shape to the porch that Edmondson so brilliantly conjures through his work, proclaiming it as a shelter from Western forces of spatiotemporal oppression, and platform for staging the moments of social connection and cultural affirmation that define a community. Moreover, Burch celebrates the porch as a dual public and private space, where what happens inside the sanctity of one’s own home comes into often sobering political dialogue with the realities of the world around it.

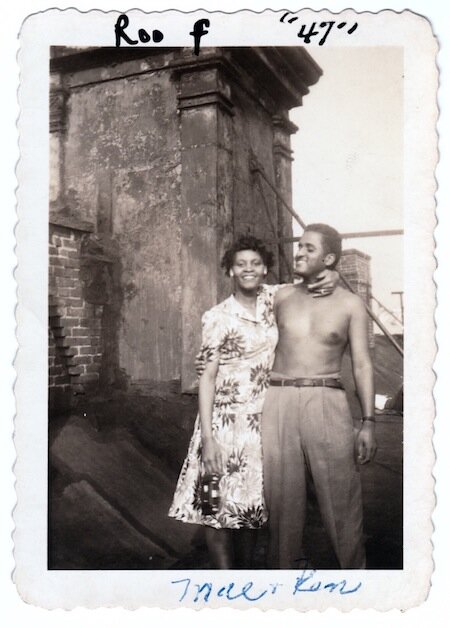

While the porch may indeed hold outsize cultural significance, Faith Ringgold’s silkscreen quilt, Tar Beach 2, 1990, stages the rooftop of a New York City brownstone as the structural backdrop for a scene of radical Black leisure and the uninhibited dreams of Cassie Louise Lightfoot (Cat. 32). A fictional character inspired by Ringgold’s own upbringing in Harlem, the young girl discovers that—through harnessing the power of her imagination—she can teleport through time and space, taking in the sights and sounds of her neighborhood and rewriting its stories from a bird’s-eye view.

She soars over the skyline on a hot summer’s night, gazing pridefully upon a scene of her own invention; her family, the Lightfoots, playing cards before enjoying a meal with their neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Honey. Laundry billows on the line while she and her brother BeBe lie on their backs gazing skywards, surrounded by vibrant green plants that delineate the rooftop “beach” from the sea of skyscrapers that encircle it like an island. The scene is at once ordinary and extraordinary, earthly and otherworldly, as the work holds the tension of embodying the unbound Black imagination while questioning the capacity for Cassie’s dreams of physical and spiritual liberation to manifest in reality. An expert visual storyteller, Ringgold claims and cultivates space for collective Black leisure to unfold, while also celebrating Cassie’s fierce self-determination and commitment to building a prismatic universe in which to see herself and her community dynamically reflected.

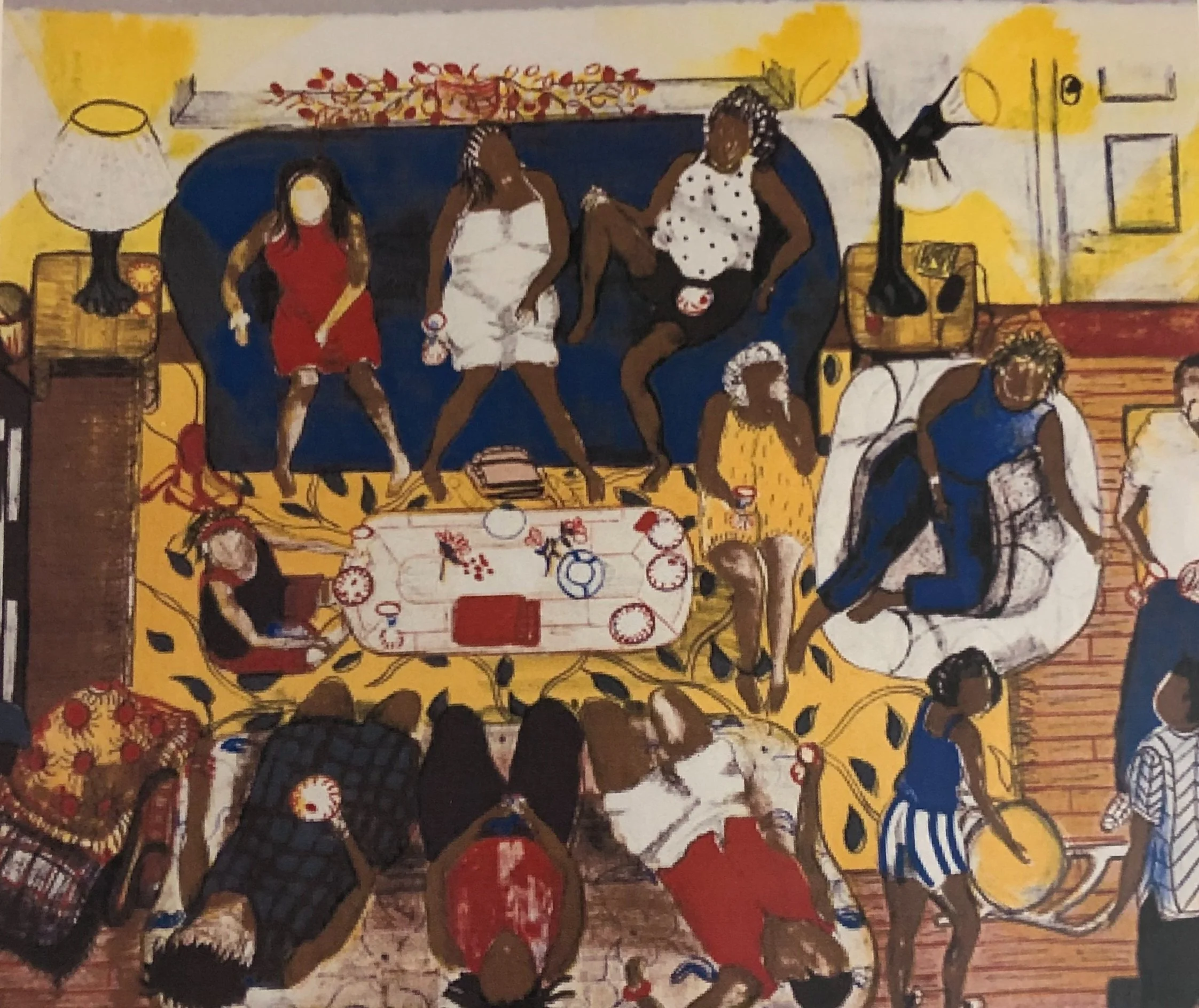

While visual storytelling is deployed as a strategy of spatiotemporal resistance across the exhibition, it uniquely manifests in Carmen Cartiness Johnson’s depictions of Black leisure. A self-taught artist, Johnson believes that “art should break boundaries and challenge rules,” whereas it should not “require the viewer to have academic education in order to understand.”[11] A true storyteller and believer in art as an effective language to communicate the profundity of quotidian Black life, her intimate paintings and drawings depict Black people reading books, enjoying cocktails, lounging on the stoop, dancing at a party, sharing a family meal, and chatting in the yard.

Johnson wholeheartedly rejects the notion that, to be a subject worthy of art, one must subscribe to the politics of respectability imposed and governed by Western standards of beauty and decorum. Instead, she carves out unapologetic space for Blackness to reflect and define itself. This refusal is embodied in her lithograph Chit Chat and Apple Martinis, 2005, where a group of friends lounge around a coffee table, enjoying each other’s company as much as the martinis in their hands (Cat. 47). While there are no features or expressions rendered on their faces—as is typical in Johnson’s work, especially her group portraits—their nonchalant body language narrates the scene, with heads craned skywards in deep relaxation. Like Ringgold’s Tar Beach 2, the scene is depicted from a bird’s-eye view, giving viewers the sense that this is an intimate moment made possible by the sanctity of the Black home and the loving community that animates it.

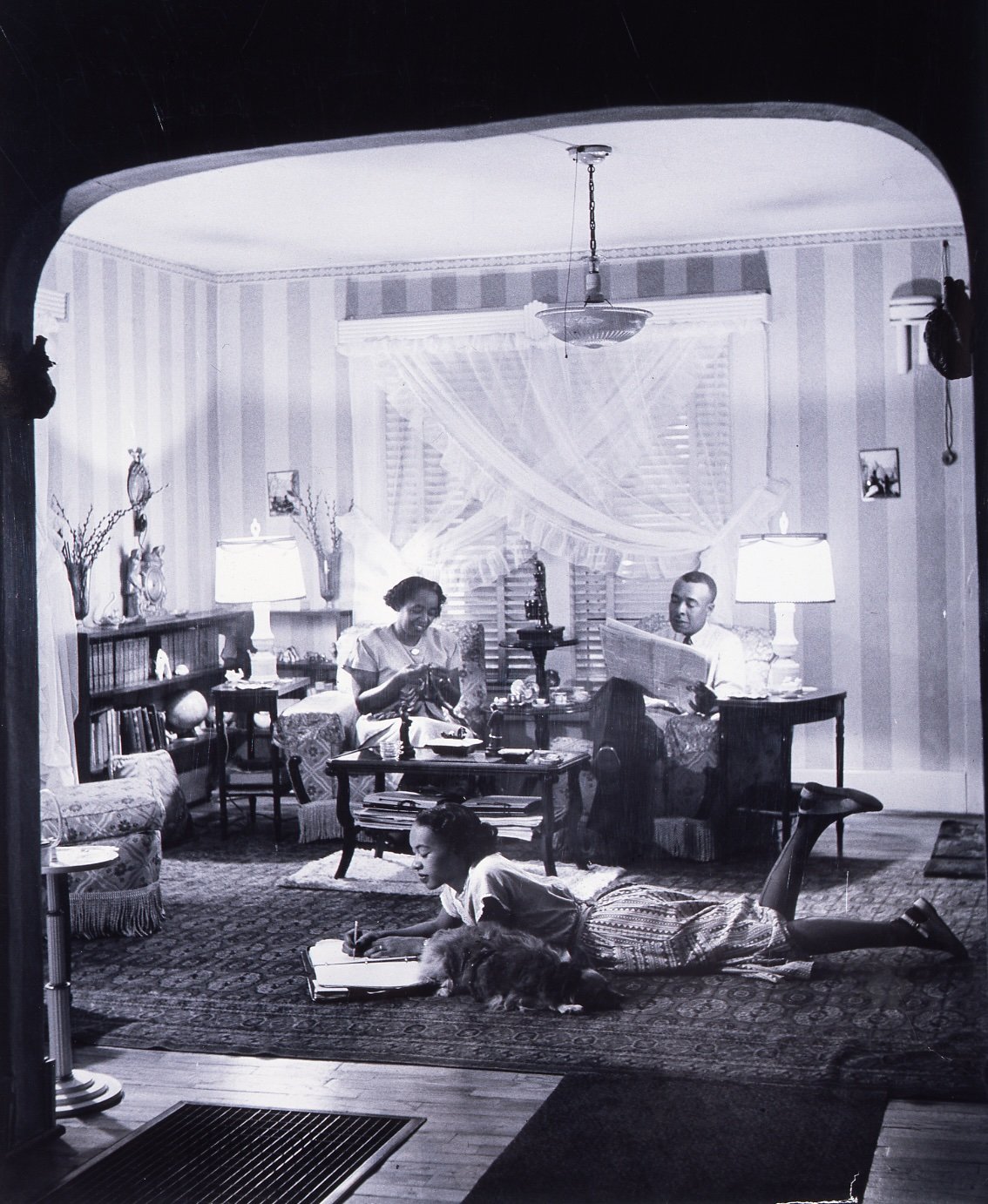

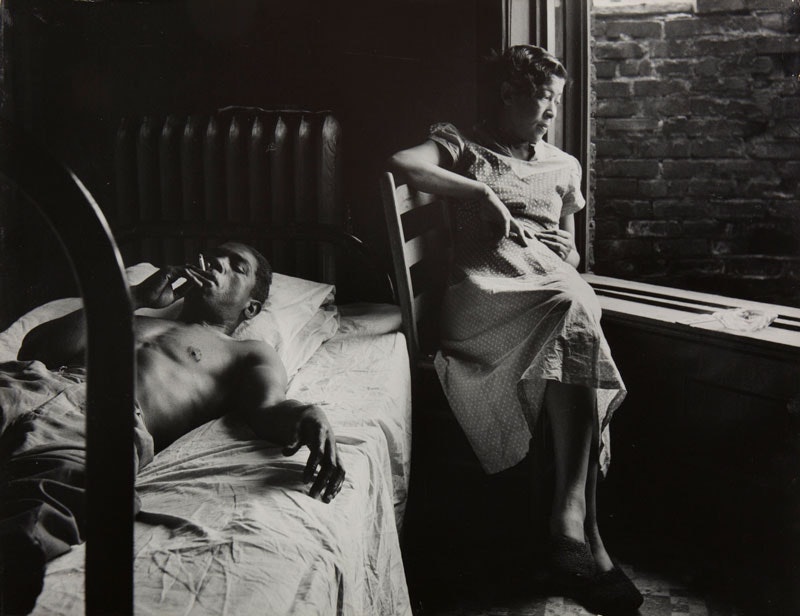

Celebrated photographer Gordon Parks—perhaps best known for his striking images that documented American culture and Black public life between the 1940s and 2000s—was similarly interested in what scenes from Black private life could communicate about our humanity. This interest was in part shaped by his humble upbringing in a family of fifteen children living under segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas. In 1950, Parks returned to his hometown while working as the first Black staff photographer at LIFE magazine. His assignment—an ultimately unpublished photo essay that was pulled to make space for more “pressing” news—was to find his classmates from the Plaza Middle School Class of 1927 and document the lasting social, professional, and economic impacts of segregation on their lives. While the assignment originated in Fort Scott, where Parks discovered that only one of his classmates, Luella Russell, remained, it soon sent him to Black neighborhoods across the country, and the stoops, porches, and parlors of long-lost friends who’d left in pursuit of something.

Fort Scott, Kansas (Family in Living Room), ca.1950, is one in the rarely seen series that documents how Black families transcended the daily spatiotemporal aggressions of racial segregation and discrimination, making a way out of no way (Cat. 6). Here, Parks captures the Russell family during a leisurely afternoon in the parlor of their Fort Scott home. He shoots the image through an arched doorway, which—coupled with the fact that the curtains are drawn and the Russells do not directly engage the camera—frames the intimacy of the moment. Luella’s teenage daughter Shirley lies on the floor, one leg kicked up fancifully, while writing in a large notebook. Luella’s husband Clarence reclines on the sofa while reading the paper as she sits next to him, smiling radiantly while engaging in a domestic craft. They are at once together in space and alone in their respective activities; the power of their connection and ease of their alone togetherness is palpable and affirms the rich interiority of the moment. However, there is something else at work here; some other essential quality of Colored People’s Time that embodies what Quashie has so poetically termed the “sovereignty of quiet.”

In the conclusion to his book, Quashie asserts, “Oneness is the interior as a place capable of discovery, of wandering, the risk and freedom to be had in being lost in one’s self. Recent scholarship has emphasized the importance of migration and movement as a way to expand what racial identities mean…what is often missing is a consideration of the mobility that is part of interiority, the inevitable human capacity to wander without ever taking a step.”[12] Here, Quashie delivers stunning language to the radiant truth emanating from this photograph; that, despite being the only family to remain in Fort Scott, perhaps the Russells need not venture so far afield—beyond rich moments such as this one, or the sanctity of the space they have co-created within it—to pursue adventure, enrichment, or opportunity.

As portals to parallel universes, the art, books, and cultural artifacts adorning their parlor exteriorize Quashie’s concept of the mobility that is part of interiority, reinforcing the sense that the Russells’ forceful collective imagination has materialized a cultural refuge; one defined both spatially and temporally on their own terms, and whose walls are impervious to the anthropological gaze of LIFE magazine’s predominately white readership. That this photograph, and the resilience and subtle resistance it exudes, was not considered newsworthy or art worthy enough to publish is perhaps a testament to the true sovereignty of Black quiet, and the sheer capacity of the Black radical imagination to resist cooptation, both knowingly and unknowingly.

While each artwork in Century indeed resists—be it overtly through the subject matter it depicts or covertly through the canonical art practices it disrupts—it would be an overstatement to claim that these works were created as acts of resistance in and of themselves. In fact, what’s more plausible is that each was produced during a moment of profound Black interiority, such as this one so transcendentally depicted by Parks; a moment where the unbridled creativity that is an utter fact of Blackness was set free to wander. That our society is still learning to see this interiority—as both a bold expression of identity and subtle act of resistance—speaks to just how limited popular portrayals of Blackness really are. If there is a call to action in this study of the aesthetics of Black spatiotemporal resistance, it is for Black people to continue to subvert time, consume space, and refuse flatness like our futures and the light of the whole world depend on it.

[1] Ronald Walcott, “Ellison, Gordone, Tolson: Some Notes on the Blues, Style & Space,” Black World Magazine (1972): 9.

[2] Zora Neal Hurston, “How it Feels to Be Colored Me,” World Tomorrow, 1928.

[3] Emilie Boone, “Reproducing the New Negro: James Van Der Zee’s Photographic Vision in Newsprint,” American Art (2020): 6.

[4] Ibid, 15.

[5] “Counting (X1992-1),” artmuseum.princeton.edu, artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/17592.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Andrianna Campbell, “Lorna Simpson,” Artforum (November 26, 2016), artforum.com/interviews/lorna-simpson-talks-about-her-recent-paintings-and-solo-exhibition-in-fort-worth-64979.

[8] Kevin Everod Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012, 133.

[9] “CAAM | Black California Dreamin’: Claiming Space at America’s Leisure Frontier,” caamuseum.org, caamuseum.org/exhibitions/2023/black-california-dreamin-african-americans-and-the-frontier-of-leisure.

[10] Burch, Audra D. S., and Wayne Lawrence. “On the Front Porch, Black Life in Full View,” New York Times, December 4, 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/12/04/us/porch-detroit-black-life.html.

[11] “Featured Artist of the Month: Carmen Cartiness Johnson Feb. 2013.” TheArtList - Art & Photo Calls for Visual Artists and Photographers., www.theartlist.com/featured-artists/feb-13-carmen-cartiness-johnson#:~:text=I%20think%20art%20should%20break.

[12] Quashie, 125–126.